____________________________

I did not expect him to answer the door in his underwear.

He was sixty-something, and I was seventeen and lacking direction. My father had just died, and high school was about to end. Instead of thinking about college, I wanted to be a boxer, like the ones my father and I had watched on television; like the one who answered the door in his boxer shorts.

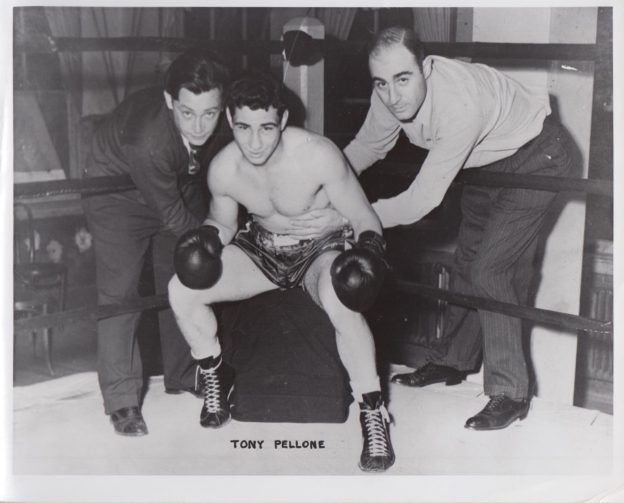

“I’m retired,” the former number one welterweight contender, Tough Tony Pellone, replied when I told him that someone he knew had sent me his way. “I closed my gym a few years ago.”

I was about to leave, dejected, but still thrilled to have met one of the brightest boxing stars from the sport’s so-called golden era. The years between the Great Depression and World War II had produced fighters accustomed to struggle and hard work. In the 1940s and 1950s, it wasn’t unusual for boxers to fight once a month.

“It was an honor to meet you,” I told him. “You were one of the guys my father talked about.”

I turned to leave. He coughed, and I looked back over my shoulder. He was still standing there, the door to his dark, one-bedroom apartment, off Kings Highway, still open.

“What’s your old man say about you fighting?”

“The grass hasn’t even grown on his gravesite,” I said.

“Give me a sec,” he said.

I had no business striking up a friendship with Tough Tony. He was older than my father, his knees hurt, he had frequent headaches, and he shared his Brooklyn apartment with a bunch of empty beer cans. He did not listen to rap or salsa music.

It was 1987 and Mike Tyson and Roberto Duran were me and my father’s favorite fighters. I would later learn that Tough Tony also admired them.

“Everybody wants to be a fighter,” he told me. “But do you wanna be an ex-fighter?”

When I answered, yes, he put down his beer can.

“Let’s go to the gym, kid.”

We jumped on the subway and headed towards the public swimming pool in Sunset Park, where, during the summers, the city put up a ring and hung some punching bags. Ramon Nieto, a corrections officer, who carried a gun in his sock and had the same flat nose as Tough Tony, was in charge.

“Got any lightweights ready for a spar?” Tough Tony asked.

The answer was “Yes…um…wait a minute…aren’t you…”

It had been years since Tough Tony had been to a gym, but all the older guys still remembered him, and they were as excited to meet him as I had been when I knocked on his door. In the 1940s and 1950s, he had boxed frequently on the Gillette Friday Night Fights on NBC and, at one time, had fought more main events at the “new” Madison Square Garden than anyone else, His first pro fight was when he was just 17, the same age I was when I met him.

Back in his days in the ring Tough Tony was the star of Greenwich Village. He hung out with Buddy Hackett and Tony Bennett and was a guest on the Who Do You Trust game show hosted by Johnny Carson. When he met Joe DiMaggio and started to introduce himself, the “Yankee Clipper” interrupted him and said, “I know you, you’re the fighter who supported his whole family. I’m a big fan of yours.”

He also knew gangsters. Vincent “The Chin” Gigante, who became head of the Genovese crime family and grew up in Sullivan Street in the Village, was a childhood friend. He introduced Tough Tony to his future wife. Another mobster, Tommy Ryan (Thomas Eboli), murdered in a mob hit in 1972, had been Tough Tony’s manager and was the Best Man at his wedding. Big Mike Miranda and Frank Costello attended almost all his fights.

Gigante became known in his later years for walking around in his pajamas on the streets of Greenwich Village.

“Is The Chin really crazy or is it an act,” I once asked.

“How should I know, I’m not a psychiatrist,” he replied.

Once the winter came, it was too hard for Tough Tony to walk up Brooklyn’s slippery slopes between Fourth and Seventh Avenues to the gym where I was training.

“They should install ski lifts on these blocks. You gotta find someone younger, someone else who can do this every day,” he told me. “Deez knees,” he added.

He soon stopped going to the gym, and my visits to his apartment were less often. About a year after I first knocked on his front door, I told him I was joining the army. “You’ll come back a man,” he said.

I went nearly three years without seeing him. When I returned to Brooklyn, I was clean shaven, had better posture, and shorter hair. He told me that I looked better. “The army did you some good,” he told me.

What had once been weekly trips to his apartment turned into three or four visits in a year. One day, he didn’t open the door. Tough Tony died at Coney Island Hospital in 1996.

By 2012, I was a part time boxing writer and historian with one published book to my name. That year, the New York State Boxing Hall of Fame was formed. I didn’t expect Tough Tony to get in during the first few years, realizing that the initial inductees were going to be international legends like Jack Dempsey and Sugar Ray Robinson. But by 2020, Tough Tony still hadn’t been chosen.

It seemed to me that somebody, or somebodies, had forgotten about the teenaged sensation called by one writer “the best thing since sliced bread.” A fast, gutsy brawler who fought them all and later trained boxers himself. He deserved to be in what he would have called the New Yawk Hall of Fame.

Though I am sure he would have been against it, I began a letter writing campaign to the committee members and flooded the internet with reminders of the onetime star. I even wrote a four-page article for the longest running boxing magazine in the world, the UK based, Boxing News.

One year later, my hard work began to pay off. I received a phone call from a board member of the Hall of Fame asking me if I would like to join their selection committee. I did, not just because of Tough Tony, but also because of my father.

It still took me another year of campaigning. “Yeah, we know he’s good but there are so many other guys too.” Only a handful each year could get in.

But, because he fought 55 main events in New York City and because he operated a gym off West 7th Street in Coney Island that helped many kids stay off the streets, Tough Tony Pellone was voted into the Hall of Fame in 2023.

The year he was enshrined was the first time in the Hall’s existence that its annual banquet was sold out. Nearly sixty of Tony’s friends and family, including his ninety-something-year-old sister, made their way to Russo’s on the Bay in Queens for the induction ceremony. His sons, nephews, grandchildren, and great grandchildren witnessed Tough Tony finally getting his due, and his old friend, no longer a teenager, had the honor of seeing it made official.

***

Jose Corpas is from Flatbush and writes about boxing and New York City, among other subjects. His books can be found on Amazon. Currently, he is trying to get a documentary made on Tough Tony. Pellone. @toughtonypellone (Photos courtesy of Pellone family.)

This is a beautiful salute to Pellone and the Pellones, but guess what -it’s also a nod to Heinz and Red Smith and Liebling, because this is what boxing writing should be but hasn’t been in a long time.

Great story, well told.

A wonderful gem of a story, the kind NY is probably filled with but rarely do we get to hear about.

Thank you for writing this article and for remembering him. Tough Tony was my Uncle.