Inside SPiN

One summer evening in 2010, I found myself leaving my job in Soho and heading uptown to SPiN, a trendy ping-pong club that had recently opened in the Flatiron District. Walking in was a bit daunting. It felt more like a hip nightclub than any ping-pong venue I’d been to or any bar I’d enjoy. But once I made my way down the stairs and past the check-in, it was comfortingly dead. I had signed up for a ten-dollar drop-in night just to scope it out. I doubted it would become my scene, but I was curious.

I passed a large internal window overlooking the subway entrance and approached the long bar in the back. Sitting there alone was a striking, older man—very tall and razor thin, with long white hair, a straw hat, and unmistakable charisma. Dapper in a period-piece way—fashionable for the moment, yet as if he’d stepped out of some earlier era, when men put on starched shirts, polished shoes and Panama hats to go out for the evening.

And yet he also looked familiar.

Then it hit me. Half a dozen years earlier I’d read a short profile—one of those back-of-the-magazine pieces—about a ping-pong hustler named Marty Reisman. The article described his famous trick shot where he would slice a lit cigarette standing on its end in half with a ping pong ball fired from across the table. What lodged in my mind, though, was an almost throwaway mention of the table-tennis clubs of the 1950s. Ping-pong clubs? I’d never known such a thing existed.

***

At that time I was living in Maplewood, New Jersey, with my husband and two kids. We had a ping-pong table in a dusty, unfinished basement where I’d taken to playing for bets with my 11-year-old son, Jake. If I won, he’d do the dishes; if he won, he wouldn’t. At first, I spotted him generous handicaps. Over time the stakes escalated, eventually leading my husband to admonish, “You can’t gamble on his skipping homework or staying home from school!” He had a point, but I was confident I could pull out the win when it counted.

Betting on ping-pong was a family tradition. Growing up, my older brother, Steve, and I played in our basement on a plywood table, wagering chores. I always lost, and then cheerfully played double-or-nothing on the entire streak, accruing a lifetime debt of bed-making and table-setting.

So when I read about real ping-pong hustlers and clubs, something sparked. I searched “table tennis clubs” online and discovered one not far from us in Westfield. In fact, it was open that very evening. At dinner, I told my son to eat up—we were going for a drive. “Grab your homework.”

As we climbed the long concrete stairs to the club, the gnip-gnop of ping-pong balls echoed thrillingly. Inside was a tribe of quirkballs who would soon become our own. Dan, who would blow a ping-pong ball into the air with his mouth and keep it hovering afloat until—clapping it into his two hands and then flinging them apart—he’d make you guess which hand to determine first serve. Rhoda, who stomped her foot aggressively with her serve and routinely picked fights. All mixed with the toxic smell of rubber cement as players ripped sponge from paddles and reglued them beneath a prominently posted NO GLUE sign.

I was directed to Chris, a lanky cyclist-runner with some leadership role at the cooperative. He grudgingly steered us to the bottom-rung table, but then warmed to us after a few games. I was decent; Jake showed promise. The nerdy guys at our low end of the room helped him with his math homework between matches.

We went every Monday night after that. We both improved, but especially Jake, who eventually had to spot me points. We took lessons; joined leagues; entered tournaments. But by high school he drifted toward Ultimate Frisbee and weed, and I lost my ping-pong partner. We still played for bets in our basement (on one of those, I won his fake ID), but gradually stopped going to the club.

***

And that’s what brought me to SPiN that night in 2010: wondering if I could recultivate a ping-pong life of my own. Immediately, I could see that SPiN was not the utilitarian gym of Westfield, nor would these be my people. It was sleek, curated with elevated baskets of orange balls by every table. Banquettes for lounging, pulsing music, neon. Fine for finance bros and models but not for misfits and fanatics.

It was also nearly empty. But there at the bar, improbably, was—perhaps—the ping pong hustler from that article: Marty Reisman.

I approached him shyly, reluctant to bother him, “Are you… Marty Reisman?”

Far from being annoyed, he seemed delighted to be recognized. “You’re the reason I started playing ping-pong,” I gushed. He invited me to sit. Though Marty wasn’t yet famous-famous, he was a local celebrity at SPiN, friendly with the owners, Susan Sarandon and Jonathan Bricklin. The bartender comped us a round.

Marty was easy to get talking. He regaled me with tales of growing up in settlement housing on the Lower East Side and a chaotic childhood, and his hustling at Lawrence’s, a table tennis club filled with the colorful underworld of a New York subculture. Ping-pong clubs, he described, were like poorly-lit churches, where no one came to pray, but everyone believed.

His adventures sounded like a novel: escaping Hong Kong with twenty pounds of gold bars stuffed in his clothes, brushes with royalty, harems, international intrigue—all accessed through ping pong. I couldn’t always follow the plot, but I didn’t want to interrupt.

Eventually he asked about me. When I told him I worked in publishing, he noted that he’d written a lengthy manuscript, a sequel to an autobiography published thirty-five years earlier. Would I be his editor? I said yes without hesitation, though in truth my publishing background was in kids’ books. Then, bartering, I asked if he’d play a little ping pong with me.

He agreed, on one condition: hardbat only, for both of us. He drew his pipped blade from a case and produced a spare sandpaper paddle for me.

By then I already understood what the equipment meant to him. Marty had been at the top of his game, a world-class champion, until one development brought his ascendance crashing to a halt—the advent of the rubber sponge paddle. Suddenly players with a fraction of his skill could bury him in spin. It was devastating. He was also morally opposed to this perversion of the game, and, willfully, never made the switch.

We played. The hardbat actually suited my game. I had solid reflexes and defense, but little spin. Marty spotted me eighteen points and beat me easily. He shared a few tips about how to loop and brush the ball, saluting at the end of your stroke. He also showed me how to bet on the game—to “make it interesting.” He called it doubling: once per game, before any point, either player could declare the next one worth two—in either direction. It was my old double-or-nothing chores wager, formalized.

A few days later, he emailed me his manuscript, delivered in a garbled text-type format. It downloaded slowly and when I converted to Word, it was enormous, over four hundred pages. The voice was unmistakably Marty’s and the story was gripping. We began meeting weekly at the club to talk through the manuscript – meetings that became as much about hearing his stories and playing ping pong as editing.

By then I no longer paid to go to SPiN. I was known as Marty’s editor and that came with privileges— free tables, comped drinks—but the real perk was sitting beside him and asking him to tell me again about the time he smuggled bricks of gold in his pants. Through all manner of shady, risky, outright lawless hustling, there was one thing Marty told me he would never do: take a dive. “The only bets I ever placed,” he told me, “were on myself.”

Time and again, he returned to his nemesis: the rubber sponge. All the things he excelled at—precision, wits, discipline—no longer counted. The new game, he bemoaned, was a pack of lies, cheating with permission.

But in many ways, after the paddle debacle, his conversion to money player was just beginning. One night he told me about a con he’d pulled in Omaha. He’d walked into a club posing as a baby-crib salesman—conservative suit, soft voice, nothing flashy—and deliberately let everyone underestimate him. He talked business, reassured his opponent, lulled him into comfort. Then, as if weary, he pulled up a chair to play seated—and squeaked out a 21–19 win. “The important thing,” Marty recounted, still enormously pleased, “is knowing when to give the other guy your confidence.”

Those days, Marty seemed perpetually on the cusp of wider recognition. Each time we met he would proudly brandish a new article or describe a documentary in the works. He was tickled when strangers recognized him.

Over time, he occasionally shared the tougher parts of his life. He admitted to the tolls of age, vision issues, surgeries, and of caring for his ailing wife, Yoshiko.

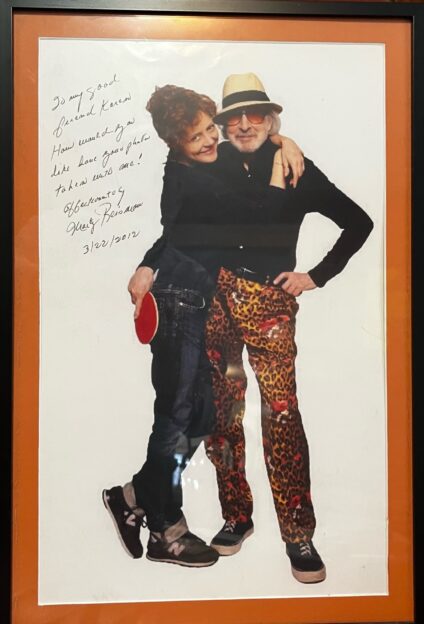

After Marty’s death in 2012, SPiN hosted a memorial service. They unveiled the Marty Room, with towering portraits and footage of him playing ping pong looping on screens. As I craned from the back of the packed room to listen to the tributes, I couldn’t stop thinking of how pleased he would have been. Susan Sarandon toasted: If you watch the videos, you see it—his life was a performance. Marty blessed us with his art and wit; he was an inspiration. So raise a glass; let’s make our lives more colorful, more kind, more playful, and live as if we are performing an art form in his memory.

Hear, hear.

***

Earlier this month—some sixteen years after we met—I sat in a darkened movie theater waiting to watch Marty Supreme at the Nitehawk in Park Slope with a mix of emotions: wistfulness that he wasn’t there to see it and perhaps a twinge of possessiveness about sharing his story and specialness with the larger world.

In the preview shorts before the feature started, the Nighthawk unexpectedly rolled a reel of the real Marty—my Marty!—playing some exhibition ping pong on the set of a daytime tv show. It was of the vintage when I knew him, eighty years old, spry, sharply dressed and still with a killer shot. I’d been prepared for Chalamet but not for the larger-than-life Marty to loom suddenly before me, unbidden. So in that way, he jumped off the screen and joined me, tucking in for Marty Supreme by my elbow.

As the film rolled, I heard his running commentary—correcting details, embellishing others, insisting that certain moments were actually much better in real life. But I believe he would have been thrilled. He would have loved being portrayed by one of the biggest movie stars on the planet, beside the beautiful Gwyneth Paltrow. He would have delighted in the attention and buzz.

The movie trades on only a small slice of Marty’s journey. His victories, defeats, hustles, and international acclaim remain largely untold to this day. But in that sliver of time when I knew him, Marty was exuberant that the world was catching up to him, that his myth would win out—as it has begun to do. I’m so glad he knew.

Chalamet’s Marty Mauser captured one truth of Marty Reisman’s essence: his singular commitment to his craft, his intensity and drive. What the movie couldn’t capture is the charming version of Marty I knew: perched on a barstool, hardbat tucked in his bag, holding court for an audience of one. The way his ego, so outsized and theatrical, was also profoundly generous—an invitation to participate in his story, to take him seriously but with a wink. To pull up a chair.

The Marty I knew was complex, contradictory, and soulful. More naturally a denizen of gritty clubs like Lawrence’s or Westfield than of SPiN. He was fiercely loyal to an obsolete paddle, contemptuous of the modern game, and deeply invested in his own legend. He was funny, vain, charming, astonishing, exhausting. Sitting next to him at the bar at SPiN, I learned that ego can be a survival strategy—that believing in yourself loudly and publicly can sometimes will a life into coherence.

Marty held firm that the only bets worth placing were on yourself. At the time, I took it as another flourish from a man who never entered a room quietly. But I see now that it also signaled a disciplined refusal to fade. Betting on yourself doesn’t mean believing you’ll always win; it means insisting that the game counts. Confidence, like a wager, is something you declare before the point is played. You make it worth two. Then you step forward and take your best shot.

***

Karen Baicker worked in publishing for decades, including serving as Publisher and Executive Director at Scholastic. Recently, her career took an unexpected spin and she now serves as General Manager of CityPickle Brooklyn Bridge. When she’s not on the pickleball court, you can find her challenging anyone willing to play a game of ping pong.

This was great! The movie version was not a likable guy – here we see a real person.

Thanks for the window into what Marty Reisman was like in real life. I will enjoy having this in mind when I finally see the movie.

Brilliant!!

Great story, Karen! Thanks!

A delightful read – a window into two creative lives!

What a marvelous story. Thanks much.

Wonderful story! Your writing brings back happy memories!

Such a vivid and captivating account of a singular personality. Thank you.