City owned buildings in the Tremont section of the Bronx.

All photos by Larry Racioppo.

—

In the summer of 1988, I applied for a job at the New York City Department of Housing Preservation and Development (HPD).

For the two years prior, I had been managing low-income properties in the Bronx and Manhattan for a management company and also working as a salesperson renting apartments and selling homes in the Bronx. But I was looking for steady employment, so I interviewed to become a “Real Property Manager” (RPM).

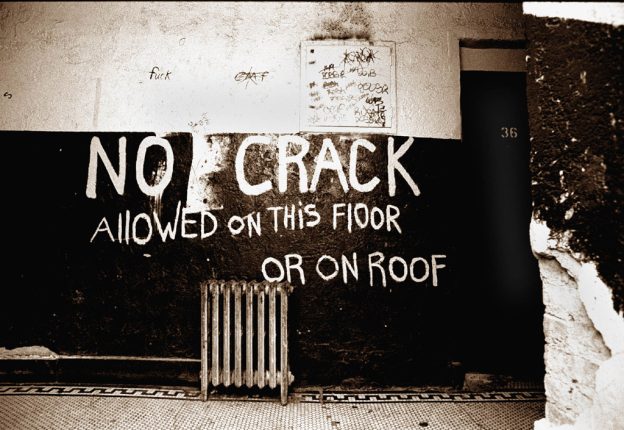

After being offered the job, I hesitated in accepting because I had some understanding that managing city owned housing was going to be difficult. The neighborhoods I’d be assigned were run down, the buildings were run down, and this was during the crack cocaine epidemic, which I knew could create dangerous situations for me. I’d be starting at the bottom of the HPD professional food chain if I took the job. Nevertheless, in September 1988 I accepted the position and was given a portfolio of about a dozen buildings in the Tremont section of the Bronx.

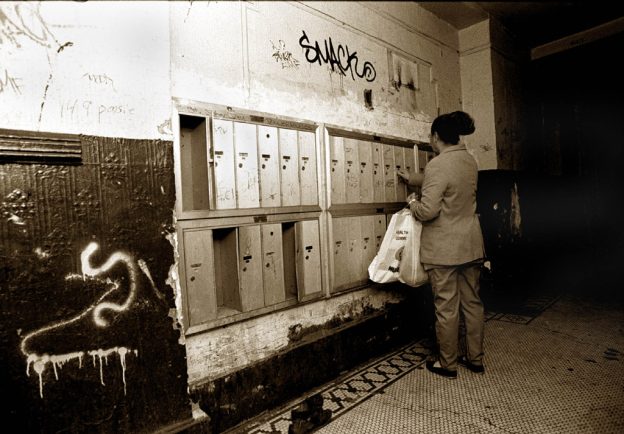

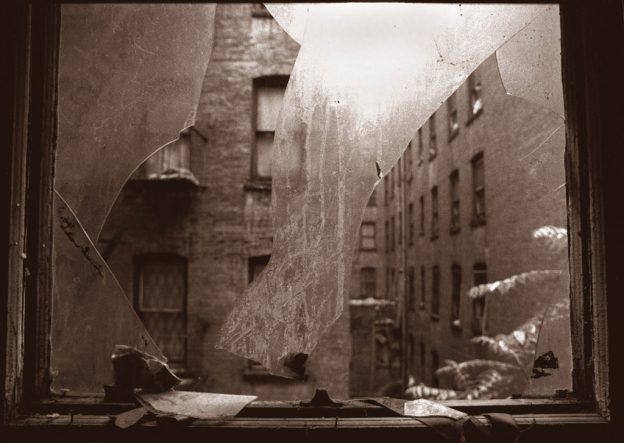

I was assigned to an office in the Bronx, and a supervisor took me to my buildings to get my feet wet. My earlier concerns and trepidation were quickly confirmed. The buildings were in a terrible state of disrepair that I had not witnessed in privately owned properties. Yards were filled with garbage and there were rodent infestations. The tenants in these buildings were living in miserable conditions.

Three of the properties had active drug dealing entrenched in a group of apartments. In the afternoon people gathered outside the buildings to purchase crack cocaine, and I would have to walk through the buyers to enter. I quickly learned to visit those buildings early in the morning to avoid the crowd that increased in size as the day wore on. The other tenants had to live with this daily terror as their buildings were controlled by organized criminal drug networks. There were several apartments that were being used to sell crack cocaine. And these were often family run enterprises. The legitimate tenants and their extended families were good people, and I sympathized with their plight. My mission was to repair the buildings and apartments as quickly as possible, clear the garbage from the yards, exterminate the rodents and eventually move the building into a capital rehabilitation program.

Part of every property manager’s job was to report illegal activities to a special HPD narcotics unit that worked with police to eradicate drug dealing, prostitution and other crime. This put me in an uncomfortable situation. Once the narcotics unit developed cases against residents in the offending apartments, arrests and evictions would follow. Not surprisingly, the tenants facing legal action would see the manager as the “snitch” who had provided information on their activities. Usually, I was able to deflect their angry accusations. The police had regular surveillance of many of these criminals, so it was not entirely clear how their activities had been exposed. The dealers often tried to bribe me to provide them with additional apartments to expand their activities.

One day in the late fall of 1988, however, I was not so lucky at deflecting blame for fingering drug dealers. During a routine property inspection at one of the buildings, in the company of another manager, I was confronted by drug dealers when visiting an apartment. The city had sent notices to several of them informing them of the allegations against them and telling them to either leave or get evicted. I had not been notified of this by the HPD legal unit and was blindsided. That day the dealers blamed me. By then, I had become familiar with several of them and told them that I had no interest in their activities. I suggested the only reason they were only accusing me was because I was white and told them that it was probably other drug dealers who had informed on them to corner the market. This was a common practice among the competing criminal enterprises in the neighborhood. A very tense situation ensued, but I had confused them enough that I was able to exit the apartment safely. That day I really had thought that it possible that I was going to be killed. And I was so shocked by what had happened that I decided to resign and leave the job.

Instead, I found out that one of my college friends had a fairly high position at HPD. After being interviewed, she offered me a different job in the agency, which I accepted. I would still have to visit these buildings but would no longer be responsible for managing them. My new position would involve going out on special assignments with an HPD photographer to document and deal with emergencies and pressing issues in properties throughout the five boroughs. This new assignment was a huge break for me. It removed me from harm’s way, and I found myself working higher up in the HPD ecosystem. My new job changed my life and put me on the road for a long career working on government assisted housing.

***

Steven Seltzer worked for 37 years in the low-income housing in both the private and non-profit sector, and for 16 years in government housing programs as a manager and housing administrator. After living for many years in the Bronx, he now resides in Maryland with his wife.