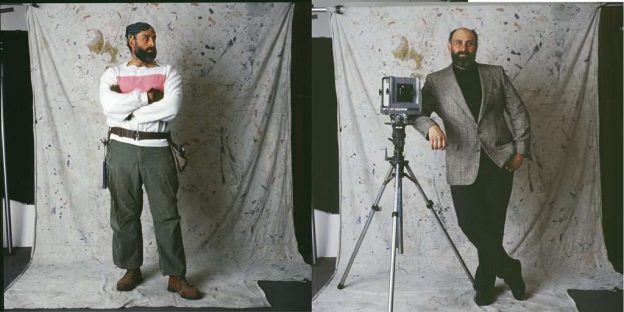

Self-portrait as a carpenter, wishing to be a photographer, 1981, in my studio.

___

As the Labor Day holiday approaches, I’ve been thinking of all the jobs I’ve had since I turned 24 in 1971, the year I began trying to “make it,” that is support myself, as a photographer in New York City.

Between 1971 and 1989, I worked as a waiter and bartender, cabdriver, photographer’s assistant, photography instructor, laborer, and carpenter. I did do some freelance photography work, but it was too sporadic to count on.

Lately, I’ve been focusing on all the different jobs I had just within the construction industry. I hadn’t known that there is an unlicensed artist-driven underground construction economy until I was brought into it by two Cooper Union grads I met at the Park Slope Food Coop in 1976. (The poet Gary Snyder recommends every artist should have at least one other way to earn a living.)

I started as a laborer with low pay, but over a nine-year period became a good enough carpenter to have my own “one man, one pickup truck” business in Park Slope. So did several of my friends, and we often collaborated on brownstone renovations.

Looking back, I remember the fun and laughs we shared more than the hard, dirty and sometimes dangerous work we did. As the Roman Stoic philosopher Seneca wrote, “What was hard to bear is sweet to remember.”

The worst and most dangerous jobs were the early ones. I laugh to myself now recalling one in SoHo which required my riding on top of an elevator in the elevator shaft because it was too small to fit the job’s 4 x 8 foot sheetrock boards inside. We sent the elevator to the basement and loaded boards on top of it, tilting them against the main cable. I held the elevator cable tightly as I leaned against the two boards on my side of the cable. My partner did the same directly across from me. We risked our lives for about ten dollars an hour.

Another job I remember because of the racism and sexism I encountered on the site, found me working for a drywall contractor on the Upper West Side. I had to leave Brooklyn at 5:30 AM to make sure I got there for the job’s 7 AM elevator ride to the 10th floor site. I was late one day and found out that latecomers had to walk up 10 flights of stairs to start the day even, though there was an elevator ready to go on the first floor.

I was one of the only white guys on a predominately Latino and Black crew. The contractor did not have a consistent pay scale and insisted that I not tell anyone what I was making—which wasn’t much.

One Friday, I witnessed one of the meanest things I’ve ever seen. At the end of the workday, it was customary to put our tool bags in a large metal “gang” box before leaving. That day the foreman stepped in front of a Latino worker and simply said “Don’t put your tools in the gang box.” He fired the worker, who was very skilled and a nice guy as well, with no warning, no severance, no unemployment. I quit soon thereafter, before it could happen to me.

This same foreman, whose lunch was a quart of Budweiser, was the source of amusement for me on several occasions. The topper was the morning the project developer made a surprise visit to the job site with a female architect. The foreman ran around the site shouting “Watch your language, there’s cunt around.”

My luck changed in 1989 when, at the age of 42, I was hired by New York City’s Department of Housing Preservation and Development (HPD). This agency was looking for a photographer who knew construction, and I was hired to photograph vacant land, distressed buildings and gut renovations throughout the city. With its modest but steady pay, vacation time and health coverage, my HPD job changed my life. I originally thought that I would work for a few months, but wound up staying for over 20 years.

I sometimes photographed construction sites accompanied by a very attractive female HPD writer. One day there was a large puddle of water filled with debris and pieces of wood blocking the entrance to the site. The project supervisor who was “hosting” us was very concerned with the safety of my partner, and escorted her her across the slippery area. When it was my turn, he ignored me. I said “What about me?” and he replied “Who gives a shit about you.” This exchange reminded of the tough but real humor I found in manual laborers.

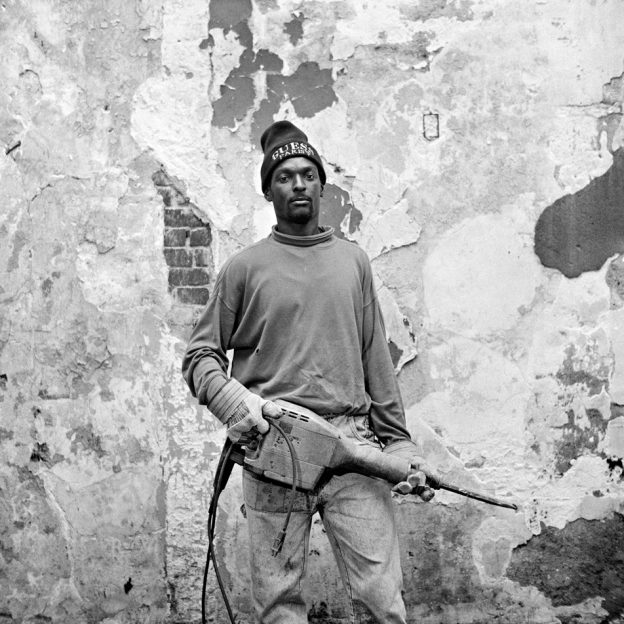

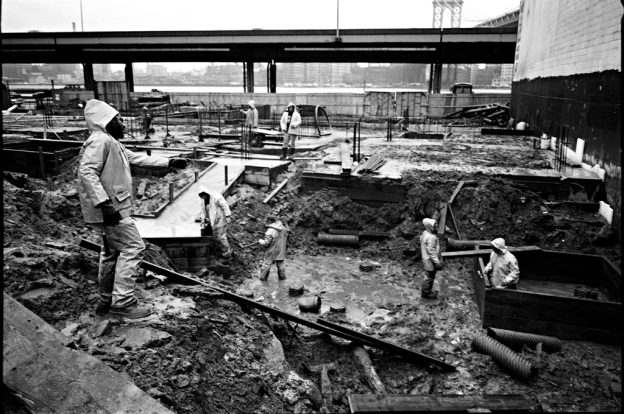

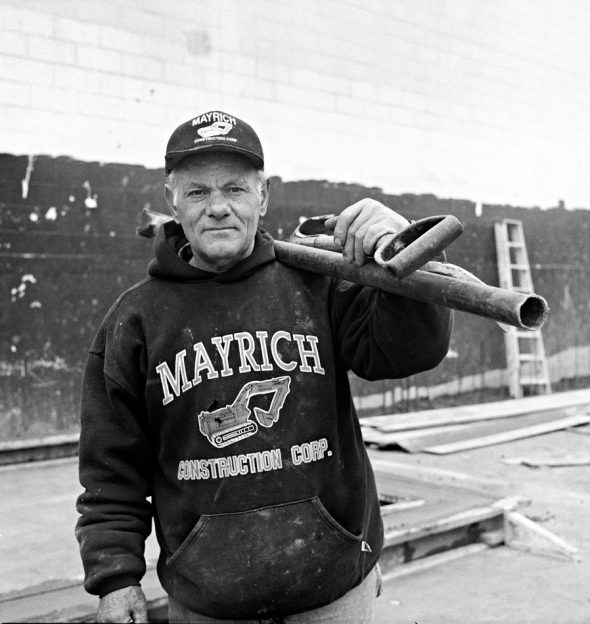

Photographing for HPD rejuvenated me, and I began working on several new personal projects. While a carpenter, I had tried to photograph the carpenters, electricians and plumbers I worked alongside. But I was disappointed with the results and eventually stopped. But at HPD, I was at construction sites to photograph, not hang sheetrock. In addition to the “official” photographs I made for HPD using a 35mm NIKON FM, I made black and white worker portraits with an old 120mm Yashica Mat twin lens camera.

Joisting Crew, East New York

——————

Man with a chipping Hammer, East New York

————–

Laborer, the Bronx

———————

Preparing building foundation, Lower Manhattan

———————

Man with tools, Lower Manhattan

***

Larry Racioppo’s new book is Here Down on Dark Earth: Loss and Remembrance in New York City (Fordham University Press), photographs by Larry Racioppo, text by Clifford Thompson and Jan Ramirez.

Racioppo’s photographs are in the collections of the Museum of the City of New York; the Brooklyn Museum; the New York Public Library; the Brooklyn Public Library; El Museo del Barrio, New York; and the National September 11 Memorial & Museum, New York.

Great insider’s view.

Wonderful photos and great telling of what it takes to live an art life.