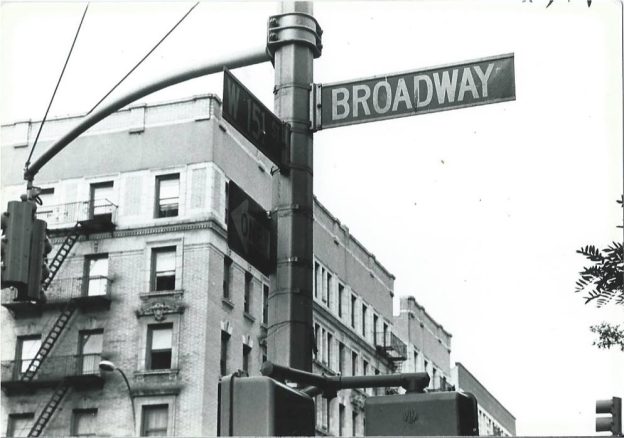

Born and raised in New York City, I spent my formative years dwelling above 110th Street.

As a tot I lived with my mom and grandmother in the Lenox Terrace, but in 1967, when I was 4, we moved to 628 West 151 Street. Living in a two-bedroom first floor apartment with wood floors except in the bathroom and kitchen, I shared a bedroom with my younger brother Carlos, who everyone called Perky.

The six-story pre-war building was beautiful and well kept. The mean-faced super, Mr. Leroy, mopped the floors every day, and the strong pine stung our noses. In the hallway, the walls and floors were marble and there were stained glass windows on both sides of the front door. A gilded mirror hung a few feet away from the elevator, and staircases on the right and left led to the first-floor apartments. Though I didn’t notice it until years later, when I was old enough to appreciate the architectural beauty of the jagged bricks and gargoyles, our building was named the River Cliff, its moniker chiseled in stone over the front door.

Standing in front of the courtyard we could see the vastness of the Hudson River. In the cold winter months, the water froze over and it looked as though you could walk across to New Jersey. At the bottom of our hill, where I once knocked my mom into the gutter while learning to ride the 5-speed Ross-Apollo bike that my stepbrother Brian handed down, we could see the George Washington Bridge from 30-blocks away. At night, when the lights were shining, it looked stunning.

One evening, as we walked to the high-rise building where Aunt Carol and Uncle Carl lived, mom excitedly said, “I love looking at that bridge. When I was a teenager, I used to walk your Aunt Bootsy’s dog on Riverside Drive, and it looked so magical.” To me, the entire neighborhood felt magical, my own personal wonderland full of music, movies and good times.

Back in those days the neighborhood was called Harlem or Sugar Hill, though years later realtors began calling it Hamilton Heights. I recently referred to the area by the latter name while talking to my homeboy Darryl Lawson, a friend and neighbor in the 1970s, who questioned me on it. “Why did you say Hamilton Heights when you know we grew-up in Harlem?”

A few blocks away, once we crossed Broadway and 155th Street, Sugar Hill melted away and Washington Heights began. Every two weeks, on Saturday mornings, mom marched me and baby brother to the Smart Style Beauty Shop on 156th and Broadway where she had a standing 8 AM appointment that went until noon. After walking past the black walls of Trinity Cemetery, where we sometimes went after church to feed the squirrels, and the gas station on the next corner, we would see mom’s beautician, Jackie, outside the shop wiping down her blue Cadillac before the start of the workday. She was a beautiful, brown-skinned woman who, even in the 1970s age of the Afro, wore her hair in a beehive. Mom was always the first customer in the chair on those Saturdays. For the four hours that we were there, me and Perky watched cartoons, begged mom for snack money, grooved to Soul Train and, if we were good, went down the block to buy chicken at Caporal’s, where you could buy the $1.50 chicken box. If a customer was blessed enough to get a receipt with a red star on it that meant you were entitled to a free box.

Even when I was an adult, whenever I was in the vicinity I always visited Jackie, who remained at the same location until 2016. “She’s like one of my aunts,” I explained to my friend Sandra when she accompanied me in 2015. I was 52 and Jackie, who was in her 70s, was still hot comb wielding, shampooing, and guiding heads under dryers. “This is Frances’s son,” she said to the few customers. “Ya’ll remember Frances, right?” Considering mom hadn’t been there since the early 1980s, none of the women knew who Jackie was talking about, but they lied anyway.

After mom’s hairdo was done, I usually wanted to stop at Hornstein’s Stationery, next door to the beauty shop. The name was misleading, because that store sold everything, including magazines, basketballs, model cars and numerous other goodies. Whenever I had to make something special (maps, posters) for class, it was where I bought construction paper, glitter and markers. When I got older Horenstein’s was one of the places where I acquired model monsters and hot rods; neither, when completed, ever looked as good as the vivid photo on the box.

Back on the block, the River Cliff had a large courtyard where the kids played Booty’s Up, jacks, and other street games, hung out, listened to the radio, and ate ice cream. That was the social center of the building, while the stoop was where Miss Joesphine sat and chatted with her friends (including my grandma Mary) while watching over the neighborhood kids. Miss Joesphine had a big family of pretty girls and one son, my friend Kyle who some people called Cheese, though I never knew why.

I was a non-athletic fat boy, better at reading comics and library books than running bases or trying to catch a football. I tried playing stickball and football but wasn’t very good at either. However, one humid August afternoon there must’ve been angels on the manhole, because I hit that pink Spalding ball to the corner and got the only stickball homerun of my lifetime. “Go Mike, go!” homeslice Beedie screamed as he leaned against a parked car. “You finally got one,” joked his brother Stanley.

Whenever we needed to get another ball, we hustled down the block to Jesus’ Candy Shop on 150th and Broadway. The store had a little bit of everything from toys to school supplies to comic books to fireworks. Jesus worked alongside his wife, and sometimes his kids were also behind the counter. His son Ricky was the one I saw most often. A nerd like me, he was into computers and Star Trek. Though he was grumpy as hell, he and I became friends for a short time. Ricky had a huge boombox and sometimes we just chilled in front of the store slurping soda, goofing on one another and listening to disco songs. “Get Off” by Foxy was one of our anthems.

In 1976 when the city’s ban on pinball machines was finally lifted after 34-years, Jesus was the first store in the hood to have them. One of the machines was an Elton John/Pinball Wizard game that I must’ve stuffed with a house payment full of quarters. Pinball Wizard was the character John had played the year before in The Who’s rock opera film Tommy. As a gonzo fan of the white soul man, I worked hard at mastering the flippers as I tried to keep the silver ball moving and grooving. Two years later, Jesus replaced the pinball machines with video games. I almost cried when it happened.

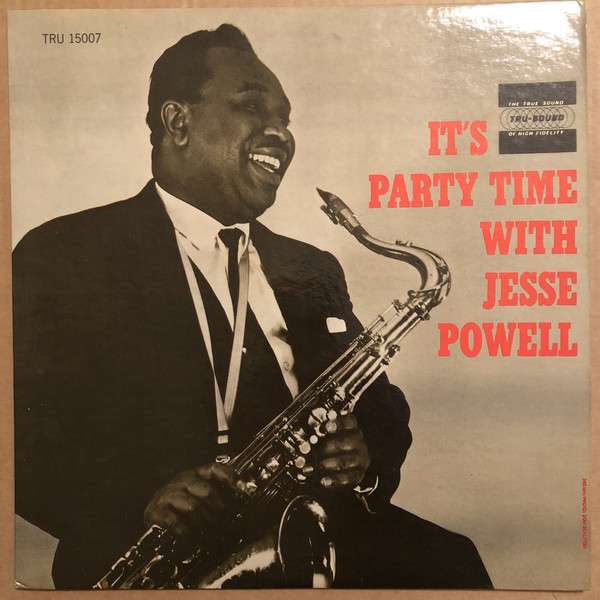

Jesse had an album cover from his jazz days that hung on the wall behind the candy counter

There were a few other stores in the community that I frequented including Jesse’s Candy Shop on 151st, where kids bought our sneak into school candy as well as the Wacky Packages that were popular product parody stickers that were the rage in 1973. The owner of the shop was a stout dark-skinned brother who I later found out was former jazz and pop saxophone player Jesse Powell who had once toured with Count Basie, Dizzy Gillespie and was the featured horn on Bobby Darin’s hit “Splish Splash” and “Mr. Lee” by The Bobbettes.

One Saturday afternoon there was a discarded refrigerator on the curb a few feet from Jesse’s. Us kids pulled it to the middle of the block, placed two rickety boards on the ends and spent the rest of the day playing Evel Knievel as we soared over the white metal box. On that block was also Goldberg’s Liquors, where mom and grandma bought their “spirits,” as some folks used to say. One night my Aunt Katie was in there buying a bottle of brandy, but as she went to pay a thief snatched the money from her extended hand and bolted out the door.

A block away, on 152nd, was Joe’s Deli, the place with the best hero sandwiches in the neighborhood. Every weekend, after catching the latest double feature at our local grindhouse the Tapia, the kind of joint full of kids watching R-rated movies, our posse went to Joe’s for our afternoon snack. I always ordered hard salami and cheese with lettuce, tomato and mustard. Joe’s sandwiches were heavenly. One morning after walking me to school, mom jaywalked in front of Joe’s. When she got to the sidewalk, a rookie from the 30th precinct called her to the side and began writing her a ticket. “But there were some young Spanish guys out there,” she told me, “and they started arguing with that cop so bad that he tore up the ticket and walked away quickly.”

Having a working mom and grandma, my brother and I went through a series of babysitters, with my favorite being Mrs. Harrison, who lived directly across the street from The Modern School, a private Black academy I attended from pre-K to 3rd grade. After school, I crossed over to the sagging tenement where Mrs. Harrison lived on the 4th floor of a walkup. She cared for a few kids including her “son” Carl, a white blond-haired child that she had in her custody, and her biological child Glen, a cool teenager who was into playing drums and photography.

Glen was always kind to the bratty brood and often let me come into his bedroom darkroom to observe him developing his arty photos. When Glen wasn’t around, I hung out with the other kids in the living room sitting on the floor watching black and white programs on the color TV. It seemed as though The Little Rascals, Abbott & Costello and Popeye cartoons were always in steady rotation. The following year, after I played sick enough times for mom to pull me out of the Modern School, it was Mrs. Harrison who helped get me into St. Catherine of Genoa on 153rd between Broadway and Amsterdam.

My stepfather Carlos Gonzales was a cool Puerto Rican who knew people throughout Harlem, be they in the valley or on the hill. He was like the mayor of those streets. He once took me and Perky to Jesse’s one afternoon for candy, and he and the fat man knew each other. Turns out daddy used to do his conk way back when he did hair at the Shalimar Barbershop. Another day he picked us up from Mrs. Harrison’s place, and he also knew her husband.

Daddy was besties with sharp as a tack Mr. Freddy, who owned my first favorite record store on 147th and Broadway. Years before I became a music critic, it was at that small shop where I bought my 45s. With posters of Al Green, Gladys Knight & the Pips, Curtis Mayfield and Isaac Hayes in the window, Mr. Freddy’s was one-stop-shopping for this soul boy. In addition to records there were also black velvet posters, incense and a paperback rack displaying books by Iceberg Slim, Donald Goines and other Holloway House scribes.

Next door to Mr. Freddy’s there was a Carvel Ice Cream parlour where we bought ice cream cakes for our birthday parties, across from the Tapia where my friends and I went on weekends to see the latest Black action movies (Gordon’s War, The Mack), kung fu/karate (Fists of Fury, 5 Fingers of Death), and whitesploitation flicks (many starring Burt Reynolds). The Tapia was one of those places where the audience talked and screamed at the characters on screen and, if the soundtrack was super bad—as in very good—they might start dancing in the aisle. In 1972 it only cost 50 cents to get in, and a few years later when the price went up to 75 cents there was almost a riot.

In the summer of 1978, when I was 15, mom decided that she, me and Perky would move to Baltimore. Grandma, thankfully, stayed at the River Cliff apartment. Attending high school (Northwestern) in our new town, I was surprised when my tolerance for “Charm City” turned into a genuine affection. Still, that didn’t stop me from being homesick and seeing almost every NYC movie released including The Warriors, Manhattan, Kramer vs. Kramer, All That Jazz, Times Square and Fame, which I saw five times.

After barely graduating in May 1981, I returned to the old hood, but so much was new to me. The Tapia had been sold, and its name was changed to The Nova; Mr. Freddy’s record store was gone, and Jesse’s candy shop had moved across the street. I was 18 years old, and the neighborhood felt as though it had lost its magic, at least for me. A few years later when crack cocaine reigned supreme, the community I once knew slipped away completely, at least until the next decade. It was a crazy time as I witnessed my beloved neighborhood become overrun with corner boys, stick-up kids and hookers.

Grandma finally moved to Baltimore to live with mom in 1993. At the time, I was in Chelsea with my publicist girlfriend Lesley. Writing for urban music magazines The Source, Vibe, Rappages and XXL in the 1990s and early aughts, I got a thrill telling my peers the many Harlem/ Sugar Hill tales I’d collected in my blunted brain. “You should write some of those stories down,” my homegirl and fellow writer Joan Morgan (When Chickenheads Come Home to Roost, 1999) said. Truthfully, I hadn’t thought about it, but once Joan said those words it was as if someone had yelled, “Let there be light.”

In the last two decades, through essays and fiction published in magazines and websites, I’ve revisited many never forgotten friends, old schools and closed businesses through words. Considering that I don’t have many pictures of the old neighborhood, those stories became my textual snapshots and helped me reclaim the magic I thought was lost. Beginning with “The Birdman of Harlem,” which takes place mostly inside Jesus Candy Shop and was originally published in 2000, I’ve written Broadway based tales that include mom’s own Sugar Hill teenage years (“Frankie Five Hundred”), grandma’s shopping addiction (“Queen of the Supermarket”) and numerous others that take place on those sweet streets of my youth.

***

Harlem born and raised scribe Michael A. Gonzales writes about neo-noir culture for CrimeReads, NYC memories for Oldster and out-of-print African-American novels for various outlets.

I live across the street from you, first in 601 then we moved to 609– moved there in 1955 from the Bronx after I graduated grammar school. I left in 1960 after finishing high school at Bishop Dubois to join the army. It was wonderful to read your story about the memories of the old neighborhood; thank you for putting them down on paper and sharing them.

Thank you for writing this! Having lived half my life up Broadway from you off 157th and RSD (inner loop), I too remember Hornstein’s, the beauty shop, and El Caporel fondly.

Don’t forget Carl’s Corner, Henry’s bar and next door the barbershop..Jessie’s restaurant was next door and Ms Louise was the waitress.

Born and raised 150 bway and

Amsterdam. I recall the diner on the downtown side 150, Mr Miller’s record shop 150 uptown side..memories

Thank you for reading “On Broadway” and I’m so glad you enjoyed it. Thank you too for sharing your own memories.

Joe: I too was supposed to go to Bishop Dubois, but it closed in 1977, the same year I graduated from St. Catherine.

Maisha: I know your old block well. I loved walking down there.

Stacey: I was a kid when Carl’s burned down, but I remember that fire well. I don’t remember Henry’s Bar, but I do recall the Palm Tree and the poolhall on the corner.

Great post. Thank you for great memories. I was very close to EMMA HARRISON your baby sitter. She was one of the most wonderful women I have ever known.

Bob Ritchie

I was born and raised on 150th between Broadway and Riverside…this article brings back memories.