Twenty years ago, almost to this very day, my tenth-grade history teacher, Mrs. Alexander, decided it would be an important lesson for us students if our class was to conduct a mock vote for president.

And without further ado, slips of paper containing the names of the candidates and their running-mates were distributed throughout the class, and Mrs. Alexander magnanimously instructed us to—of course feel free to choose whomever we wanted to choose—but to of course be sure that we did not write our names on our ballot. Voting is a confidential, private act, she said, and it was no one’s business but our own whom we selected. And then she reminded us that we had our Founding Fathers to thank for it. I found no solace in this built-in anonymity.

I was a shy boy, I had few friends, I was not particularly athletic, I was not particularly good looking, plus I had a strange, unpronouncable name, plus I was too thin, and plus I wore used clothing. My classmates, on the other hand, were white, well-heeled and unambiguously American, and as you might imagine, any activity that involved traversing the wall of silent-student caused me great dread—but none caused me greater dread than now having to cast a vote.

We students mechanically set about at the task at hand, choosing quickly among the options presented, and when we were finished we carefully folded our faux-ballots in half and passed them back up front to Mrs. Alexander who shuffled them extravagantly for all of us to see.

“Let there be no doubt,” she said.

Then she redistributed them to us.

And one by one, we read off the name of the candidate that had been ticked off on the anonymous ballot we now held in our hands. Reagan, Mondale, Reagan, Mondale, Reagan, Mondale, down the row of students, then down another row, then down my row, and I called off the name chosen on the ballot, and then on, one after the other, intoning, Reagan, Mondale, until there came an abrupt pause and the rhythm broke. It was a deadly pause for me, because I knew that I was the one responsible for it and I instantly regretted what I had done.

The election of 1984 was not too terribly different from the election of today. The Democratic challenger was labeled a flip-flopper and the Republican incumbent was condemned for his public gaffes. There was great concern over the religious leanings of the candidates and whether or not they were born-again Christians and whether or not that would influence their policy making. The Republican was harshly criticized for not accepting responsibility for a terrorist bombing that had occurred on his watch. There was also much concern and confusion over the candidate’s views on abortion and if they would support a constitutional amendment outlawing it, and what types of Supreme Court Justices they would appoint, and what was to be done about the ballooning deficit, which then was about 200 billion dollars. That was 1984.

And in my history class Constance Reiter, whose name I’ve remembered all these years for some reason, stared down at the ballot on her desk, blushing.

“I don’t know,” she said very softly, “I don’t know, but I think this might be a joke.” And then she looked up at loss. “Someone has written in the name of someone for president.”

“Well, go on, Constance, read what the ballot says,” said Mrs. Alexander, pleased that the paradigm of voting had been organically extended to include this possibility.

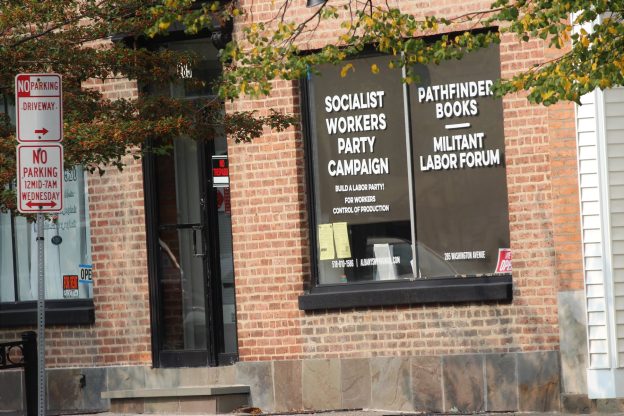

So Constance Reiter read the ballot aloud for everyone to hear: “Mel Mason,” she said, “president.” And then she added: “Socialist Workers Party.”

There was another pause, a stop, as if everyone in the room had inhaled at the same time and held their breath at the same time, and then, on cue, as if orchestrated by an invisible maestro, the entire class exhaled simultaneously and erupted with laughter, long, loud, deep laughter, everyone in the room laughed, including Mrs. Alexander.

**

I am the son of a father who is a devout orthodox fundamentalist communist. His life resembles the life of someone who is single-minded in their pursuit. For instance, if you were, by chance, to visit his apartment on Greenwood Avenue in Brooklyn like I have in recent years, you would be forgiven for thinking that it was inhabited either by a college student in his first year of undergrad or a monk. You would notice that my father’s bed is a mattress on the floor, that the lone plant has died long ago, that my father does not own a couch, that the bathroom has not been cleaned since he moved in, and that the bottom shelf in his bookcase contains the collected works of Lenin, in hard cover, which includes letters to relatives and which runs to forty-five volumes, and that the top shelf contains the collected works of Marx and Engels, which runs to forty-nine volumes, and also in hard cover.

Were you ever to meet him he would, roughly within five minutes of being introduced to you, begin to hold forth on one or more of the following subjects: the condition of peasants and workers in the United States, the Russian Revolution, the Cuban Revolution, Lenin, Trotsky, Che, Thomas Sankara, the recent coal miners’ strike in Utah, the recent meat packers’ strike in Toronto, and the recent soap factory strike in Scotland. That’s a partial list. And if you had met him prior to the election he would have also undoubtedly talked to you about Róger Calero, the 2004 presidential candidate on the Socialist Workers Party ticket. And then he would have reminded you that the Democrats and Republicans are both imperialist, capitalist parties, they are the twin parties of war and depression, and that they do not, quote, point the way forward for working people, end quote. He would have included Ralph Nader with them, as well. Revolution is the only way to bring about true change for the working class, he would have told you in a pedantic way, yet with enough of a touch of charm that might have caused you to overlook the tone of his voice that revealed he was operating under the assumption that he knows everything and you know absolutely nothing.

And because a capitalist society can only be reformed by being overthrown, my father had no choice but to abandon my mother and me when I was nine months old, without appearing again for eighteen years.

“He went off to fight for a world socialist revolution,” my mother would later tell me in a fairy-tale sort of way, as if this explanation would provide me with great comfort. And in order to please her, I pretended that it did.

My mother being a single woman with a child and a low paying job did what most women would do in her situation, she too became a devout orthodox fundamentalist communist. It was an instant extended family of sympathetic, like-minded people, who would throw a Halloween party and a New Year’s Eve party, and in the summer a cookout with a softball game, and who could help you with that broken light fixture or a truck and an extra set of hands if you needed to move. And being devout she, of course, proceeded to raise her son so he would grow up to be devout as well. Or in other words, to be like his father. She took her son to Socialist Workers Party meetings on Friday and Sunday nights, to Socialist Workers Party conferences, to Socialist Workers Party book sales, to newspaper sales, to rummage sales, to leaflettings, to campaigns, to rallies, to demonstrations, and to prisons to meet political prisoners.

When I was a little boy I would ask my mother when exactly the world socialist revolution would take place.

“Soon,” my mother would say.

“Will I be nine years old?” I’d ask.

“Well, no,” my mother would say. “The revolution’s going to take a bit longer than that.”

“Will I be ten years old?”

“No.”

“Will I be eleven?”

“No.”

“Will I be eighteen?”

And then she’d say: “Yes. You’ll be eighteen. When you’re eighteen the revolution will take place.”

And then I would go outside and play.

My mother and I were a Marxist family. Our denomination was Trotskyite, and our bible, besides being Capital and the Communist Manifesto which every and all communists adhere to, was “The Militant” newspaper. A roughly sixteen page socialist newsweekly published, as the nameplate will tell you, “in the interests of working people.” And if my father were here with us now, he might try to sell you a subscription, five dollars for twelve weeks is the introductory rate.

I was raised to believe that there was only one way to think and that way was the Socialist Workers Party way, and which by logical extension was my father’s way of thinking. So in this way I became adept at father-think and by doing so he continued to exist among my mother and me. Those that thought differently were either to be convinced, ignored or, if those failed, derided. If my mother and I, for instance, passed a group of people campaigning for another organization, the Communist Party, say, or the Democratic Party, my mother would fall silent and stare straight ahead with a look akin to that of a Star-Bellied Sneech. And since I was her son I learned to affect that air as well.

When I was twelve years old I had something like a religious epiphany. I was sitting cross-legged on the living room floor reading the articles in “The Militant,” not understanding what was being said in them, but understanding implicitly that they were good and right and smart, and I was overcome suddenly by the realization of how amazing it was that I had by absolute chance been born into a family that thought all the right things, all the correct things. And I thought that I was the luckiest boy in the world.

The unlucky part, however, of having such a minority perspective of the world as a child was that I learned early on to hide it from others, and painstakingly cover up that part of myself. Privately I desperately wanted to belong and be normal and be a Democrat or Republican, and be pro-American and pro-business, and I found myself going through my days internally pretending I didn’t think what I thought. Twenty years ago the classroom vote painfully reminded me of what the world thought about my mother’s and father’s ideas. It has occurred to me now, though, that it had been completely within my power to cast a vote for Reagan or Mondale. My mother and father weren’t in the class with me, they would have never known that I had betrayed them. The training wheels my mother had so carefully constructed for me had been taken off and I had dutifully acted as a surrogate for my parents and championed their deepest desires. I had become the architect of my own isolation.

This brings us all the way to our present and our present-day election. One week prior to November 2nd I had lunch with a good friend, a Democrat, who was beside himself with the prospect that Kerry might not win. I scoffed at his concern. Of course, there was no difference between the Democrats and the Republicans, I told him, each were equally awful and equally to blame for the state of affairs. And shouldn’t this be plain to everyone by now? Of course, I would not vote for Kerry. Of course, I would not make phone calls for Kerry. I was pedantic, but charming. My friend conceded that while it was true both candidates might be awful, it was also true that one was much more awful than the other. I conceded nothing.

I pointed out that the Clinton administration was responsible for so many policies that my Democratic friends at the time had either minimized, forgotten, excused, ignored, supported, or never known about. Joint Vision 2020, the Anti-Terrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act, the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act, the Financial Services Act, the Defense of Marriage Act, the Gag Rule, the Hyde Amendment, regime change in Iraq as official U.S. policy, and 1.3 billion dollars to fund the military in Columbia. To name a few. Where was the outrage for those Democratic policies? And where was the long view of history connecting the policies of the Bush Administration, that everyone deplored, with the Clinton policies that had laid the groundwork and made them possible. If the knife cuts, I told my friend, it cuts two ways.

But as I argued with my friend over our lunch, a very persistent and unsettling thought began to work its way up into my consciousness, that the knife that cuts two ways, can also cut three ways. I became acutely aware that prior to saying anything I was, in my mind, checking in with my father.

“What should I say next, Pop?” I would ask him.

And then my father would tell me. “Say this to him,” he would say.

And then I would say it.

“Did I do good,” Pop?

And my father would say, “You did good.”

This is how I have been connecting to my absent father since I was a little boy. By visiting him in the ether of the world socialist revolution. All of his hopes and aspirations and emotions and loves and losses are tied up into that one abstract concept. And now, at age thirty-five, I no longer had any way of knowing what it was I thought from what it was my father thought. We had become one. And I had to admit to myself, not to my friend, but to myself, that while the facts about the Clinton Administration were all true, I had selectively chosen them to support a conclusion that had been bequeathed to me at birth.

And as a general malaise fell over New York City on November 3rd, it occurred to me that if I had not been born into the specific household that I had been born into I would feel the malaise too. And it further occurred to me that this island that I loved, that I admired and respected, and wanted to preserve and protect, had overwhelmingly, by eight-two percent, voted for a candidate that I was opposed to. All my friends had voted for Kerry, my therapist had voted for Kerry, my girlfriend, her parents, my co-workers, my neighbors, on and on. Could the 468,841 really be wrong? Could the 566 who voted for the Socialist Workers Party candidate Róger Calero really be right? I had by an act of providence been born into that select nine one hundredths of one percent of the voting population of Manhattan. But what, I wondered, if I hadn’t? What if my father was a Democrat, or a Catholic, or a Mormon, or a Nazi, or a flat-earther? What words of wisdom would I now be offering my friend?

**

After my father abandoned us, my mother took to hoarding “The Militant.” Week by week she saved them, possibly as a way to preserve my father’s legacy. Forty-eight issues a year for five years, then ten years, then fifteen years. My mother kept them in the closet by the front door of our apartment. It was our luck that the architect had designed the closet door to open in, rather than out, depriving us of about fifty percent of the space inside the closet. My mother got around this by simply keeping the closet door open at all times, so if you were ever to pay us a visit the first thing you would see upon entering our apartment was my mother’s shabby coat hanging from the hook on the door and stacks and stacks of “The Militant” piled all the way to the very edge of the closet and against the wide open closet door.

Once, to while away the time during the Christmas break I turned thirteen, I dragged out all of “The Militants” and put them in chronological order. The task took several days. Many were yellow and faded and covered with dust. But there they all were. 1969, 1970, 1971. The Vietnam War, Roe v. Wade, Watergate, the Equal Rights Amendment, the Iranian Hostage crisis. Each issue was a week in our life. A week without my father, her husband, a week moving further away from the time when he had been with us and closer to that glorious revolution that we were so sure was to come and with it all its attendant happiness and sunshine and warmth and love. When I was done organizing all of “The Militants”, my mother thanked me for my hard work and then tied bundles of them together with twine and stacked them back in the closet with the door again pinned wide open. And that’s how they’ve remained ever since.

**

sayrafiezadeh@yahoo.com