I didn’t pay much attention to Zim Scorpio at first. The container ship was far away — little more than a dark outline on the water. I’d passed plenty of freighters in far worse wind and felt I had enough breeze and time to cross the narrow Kill Van Kull from New Jersey toward Staten Island. But midway across, something changed. Her fresh black paint came into focus — she was brand new — and my Sunfish sailboat was still sitting squarely in the middle of her very wide bow. A warning I’d learned surfaced sharply: if the angle between you and an approaching vessel doesn’t change, you’re on a collision course.

Having a sailboat and a trailer let me explore waterways as far south as Barnegat Bay and as far north as Lake George. But you don’t need to follow Natty Bumppo into the Adirondacks to find an adventure. In the 17th century, Captain Christopher Billopp claimed Staten Island for New York by sailing around it in less than 24 hours. For more than 350 years afterward, no one had bothered to race or even cruise around the city’s smallest borough. Then, in July 2025, Staten Island Live reported on my plan to break that long pause.

Sailing a Sunfish for hours is physically demanding even when everything goes right. There’s no back support, nowhere to stretch your legs, and long periods where the body is locked into a single position. It only gets harder with age, and my waiting any longer wouldn’t make it more prudent — just less likely. If I was going to launch a boat small enough to lift onto a car roof into some of the busiest commercial shipping lanes on the East Coast, this was the time to do it.

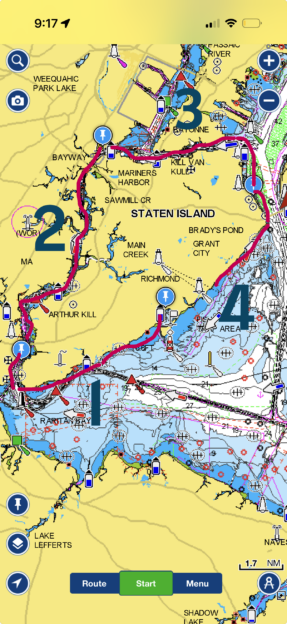

First Leg: South Shore

I launched from the Great Kills Harbor ramp on a warm August morning. In New York, the August wind is usually kinder than early summer’s fickle breezes and gentler than the sustained blows of fall. Passing the beacon tower marking the harbor entrance, I headed southwest toward Raritan Bay.

The southern coast of Staten Island is undeniably pretty. Trees, green lawns, sandy beaches, and the occasional mansion lined my starboard side. Wolfe’s Pond Beach — reddish sand, lifeguard chairs centered like props, tall trees rising behind — looked like a scene arranged for a painting. I slipped past fishing boats and their smaller cousins, the motorized kayaks. “Does your boat have an engine?” I was asked that at least half a dozen times on my first day.

The New Jersey shoreline drew nearer. With the Great Beds Lighthouse off my port side, I passed Tottenville. Across the water lay Perth Amboy — a town with two names — marking the entrance to Arthur Kill, the waterway that runs along western Staten Island and New Jersey.

Soon after, I arrived at the Port Atlantic Marina, whose owner, Greg, had agreed to let me leave my boat for the night. Greg and Frank, the marina manager, were no strangers to unorthodox visitors. At the time, they were hosting two young women who had ridden Jet Skis all the way from Florida. Their plan was to continue up the Hudson River, cut through the Erie Canal into the Great Lakes, and then ride down the Mississippi River to the Gulf of Texas.

Greg and Frank provided me with a knife, flashlight, mug, and a key to the gate so I could cast off whenever I wished. They refused to accept any payment. The first leg had gone better than I expected.

Second Leg: Arthur Kill

The next morning, I cast off quietly from Atlantic Marina. I had just settled on my new course when Arthur Kill delivered its version of a greeting — a barge wake rolled over the Sunfish and flooded the cockpit. I passed under the Outerbridge, the gateway to the Jersey Shore, and headed north. The New Jersey shoreline was lined with terminals, factories, and storage yards for nearly the entire ten-mile stretch. On the Staten Island side, trees and houses gradually gave way to empty tracts separated from the water by fencing.

I sailed past the Isle of Meadows and Prall’s Island, and a lone fishing boat setting traps for whatever dwelled below. Soon heavy industry surrounded me on all sides. Loud banging and drilling echoed across the channel, yet not a single person was visible. Noise came from above as well — every few minutes a plane, one wing dipped, made its descending turn toward Newark Airport. The whole scene felt like a glimpse from a sci-fi novel — a post-human world where machines are run by machines.

Arthur Kill Lift Bridge

I passed under the Goethals Bridge and then the Arthur Kill Vertical Lift Bridge, which looked like a giant adjustable headboard. It was time to dock. My first choice was a yacht club on the Staten Island side, but I was told that for my Sunfish to enter, I’d need signed consent from every member.

Across the channel, on the New Jersey side, was Elizabeth Marina, which accommodated only powerboats and Jet Skis. Luis, the manager, kindly allowed me to use the ramp after I explained that my Sunfish was basically a Jet Ski, only a little longer. Elizabeth Marina was impossible to miss: Jet Skis blasted out of it like Smokers from the movie Waterworld, and music carried far across the water. Not knowing what waited inside, I sailed straight in and immediately took down the sail — there wasn’t much space to maneuver. Arthur Kill was behind me now.

Third Leg: Kill Van Kull and the Narrows

My first foray out of Elizabeth Marina didn’t last long. The wind was a full 17–20 knots and sailing quickly turned into a balancing act. I was focused more on preventing a capsize than on making any real progress. The only consolation was the impressive speed the Sunfish generated in those conditions. I returned back inside the safety of the marina in no time.

A Sunfish sail can’t be reefed, but there is another way to depower it: the Jens Rig. You shorten the mast and bring the sail down and forward, giving the boat more stability in stronger wind. With that setup, my next attempt carried me past Newark Bay and the Bayonne Bridge. Tugboats moved back and forth along their routes, and by now they had grown accustomed to my presence. Some even answered my wave with a soft, friendly horn blast.

(Verrazano Narrows Bridge photo by Stas Holodnak)

Soon I saw the Staten Island Ferry slicing through the Narrows, and beyond it, brief glimpses of my beloved Brooklyn. That view vanished abruptly when a Maersk container ship began pulling away from the dock. At the same moment, the wind slackened, and sailing turned into a tug-of-war between the fading breeze and the incoming current. I drifted past a Mobil gas station several times, only for the current to drag me right back toward it. The Maersk was edging closer while the Sunfish had almost no propulsion left.

The gas station sat beside a small pebble beach and a haphazard dock held up by a few weathered wooden piles. I grounded the Sunfish there just in time. Moments later, another container ship appeared from the opposite direction, rounding the bend and cutting across the very spot where the Verrazano Narrows Bridge had been five minutes earlier. Getting out of the water had been a good idea.

A flock of geese patrolled the beach and the patches of grass beside it. They ignored me, and I kept my distance. After an hour, the wind picked up again. I drained the cockpit and cast off. The breeze was steady, and for once, no container ships were in sight. But as I checked my rigging, I noticed the mainsheet running alongside the boom instead of beneath it. I could still tack and gybe, but it wasn’t right. I turned back to Geese Landing — the name I’d already given the place. If I was going to reach the Narrows, the most challenging part of the trip, I wanted the boat rigged properly.

I fixed the rigging and drained the cockpit once more. But as soon as I tried to cast off, a barge wake rolled in and flooded the cockpit again. After several more unsuccessful attempts, I was exhausted. I dragged the boat as far up the beach as I could.

Mo, the manager of the Mobil gas station and the adjacent self-wash, kindly allowed me to store the sail and rigging inside. As I was securing the boat, I finally understood the purpose of that makeshift dock. A Jet Ski pulled in, its rider tying it to the pilings before heading to the station with an empty one-gallon bottle. He made multiple trips back and forth. I couldn’t help thinking he would need a lot of those bottles to reach the Mississippi River.

I came back the next morning to find the geese wandering around and my boat sitting six feet from the water. Low tide. I could launch from there and deal with the wakes again, or I could take the boat back to Elizabeth Marina for a cleaner start. I chose extra sailing over extra effort. Two men washing their cars helped me load the Sunfish onto the trailer, and soon I was on my way back to Kill Van Kull once more.

The third try was the charm. The wind settled at about ten knots, and the outgoing current worked in my favor. I waved — and even shouted a greeting — at the geese as I sailed past them. I met Zim Scorpio soon after. For a while we were clearly on a collision course, her horn blasting repeatedly. Tugboats flanked her on both sides. I resisted the instinct to grab the oar and start paddling. The wind was steady, and I was moving.

Zim Scorpio and my Sunfish passed port to port. The crew enthusiastically shouted rhetorical questions at me. A few seconds later, the ship was part of the past. My attention shifted to the next challenge: crossing the paths of the Staten Island ferries.

The sudden appearance of sharp chop marked the invisible line where Kill Van Kull, the Narrows, and the Hudson River Bay meet. The outgoing current collided with the incoming wind. Holding the mainsheet became difficult; the Sunfish heeled hard and slid sideways. I hadn’t expected that much resistance and quickly retreated to the relative protection of Kill Van Kull.

I began looking for a place to come ashore, but nothing resembled Geese Landing. Piles of garbage lay along the shoreline, which was separated from the outside world by thick shrubbery. A few people wandered aimlessly nearby. It didn’t feel like a safe environment for my Sunfish — or for me. What a stark contrast to the peaceful southern shore.

Garbage wasn’t confined to the land; it floated freely through the Kill Van Kull as well. The water there isn’t blue or green but the color of industry — opaque, restless, and carrying things you don’t want to imagine touching your skin. I thought about the intense but clean water of the Narrows I had just sailed into, and the tall towers of the Verrazzano Bridge. I turned the boat back toward the Narrows. I wasn’t focused on the Staten Island Ferry anymore — only on the chop, the sail trim, and balance.

I had a window: one ferry had just left Staten Island, and the other was still somewhere near the Whitehall Terminal. A cruise ship lurked a mile away, but there was plenty of water for everyone. I pushed on despite the chop and gradually adjusted to it. The spell of Kill Van Kull had broken. I was in the Narrows, where the water was anything but narrow.

I glided south. The chop was gone. For years, walking along the Shore Road Promenade in Brooklyn, I had dreamed of sailing beside it, and now I finally was. But daylight was fading. The Verrazzano Bridge was drawing near, night was approaching, and with the current running out I risked being carried into open water.

(Than and Roy photo by Stas Holodnak)

On the Staten Island side, I noticed a small beach. Men were fishing, women lounged in beach chairs, and children ran along the shore. This was Buono Beach. Two anglers, Than and Roy, helped me pull the boat above the high-tide line while their kids played with the sail. The last and largest bridge — the Verrazzano — would have to wait.

Fourth Leg: The Home Stretch

The next afternoon, I began the final leg of my journey. I passed Fort Wadsworth and the Verrazzano Bridge — a monolithic structure that feels intimidating when you look up at it from the water. Soon, the bridge and the Narrows were a distant backdrop. I continued sailing southwest for another hour. Then the wind began to slacken, and I decided to stop. Surprisingly, this was when I made my biggest mistake.

I treated the beach as if it were a proper ramp, assuming my all-wheel-drive SUV would have no trouble with wet sand. Instead, the car sank as the tide was coming in, and eventually a Caterpillar bulldozer had to pull it back onto dry land. I had always assumed the trailer needed to be lowered into the water to guide the boat on. I was genuinely surprised when the Caterpillar crew performed the entire operation on dry ground: they lifted just the bow of the Sunfish onto the trailer and then used the winch to pull the rest of the boat aboard.

I stopped about two miles from where I had started my Staten Island journey. I had sailed under every bridge and rounded every corner. The trip unfolded in four legs, each taking less than four hours. Under the right conditions, a nonstop circumnavigation is entirely possible — perhaps even fast enough to beat Captain Billopp’s record.

It feels good to watch a sail glide over the water. That may be why people — boat owners, anglers, and passersby — showed such an easy readiness to be part of the journey. I smiled when I saw Luis from Elizabeth Marina bring out an oar the length of my boat after I mentioned I’d lost my small paddle. Experiencing that kind of human warmth was its own discovery.

***

Stas Holodnak, originally from Ukraine, lives in Brooklyn, New York. He has written anintroduction to sailing for children and their parents.