Every other Friday — when I was six to seven years old — my Uncle Lou would pick me up from school to take me to my dad’s for the weekend. He would wait in the parking lot of my Montessori elementary school in Stamford, Connecticut, idling in his Lincoln sedan, as though he were my elderly chauffeur, emerging once I reached the car to envelop me in a musky, cologne-soaked hug.

My grandparents were in Florida and California. Uncle Lou — who was really my dad’s uncle and, thus, my great uncle — was the closest thing I had to a local grandfather. I was still a child, but I knew that his wife was Shirley and his three kids (my cousins once removed) were Phyllis, Sandy and Phillip. I knew that he fought in the Second World War and was taken prisoner, for which he was revered in our family. I knew that when my dad was a kid Uncle Lou’s propensity for threatening to lock my dad and his cousins in the cellar of my great-grandmother’s house earned him the moniker Lock-‘Em-in-the-Cellar Louie. And I knew he worked at my dad’s financial-planning firm.

What I remember most was the time we spent together on those drives across the New York metropolitan area during Friday rush hour. A trip that normally would have taken forty-five minutes — from my school in Stamford through Westchester County and to my dad’s Suffern office in Rockland County — took close to two hours, which meant that entertainment and sustenance were required.

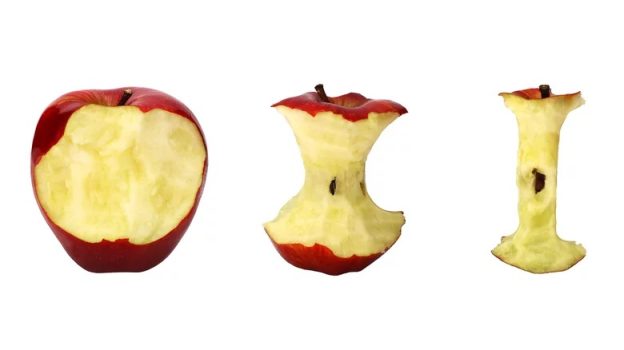

So, Uncle Lou always had apples for us to eat and stories to tell. Perhaps out of a Depression-era sense of what a little boy should know, he taught me how to eat an apple properly — which meant consuming the whole thing, core and all (but not the seeds). Even at that age the practice struck me as unnecessary, mostly because there was no shortage of apples to eat. But I was intrigued. As a boy fascinated by nature and survival, eating every bit of something, as if I was on a journey through untamed wilderness, sparked my imagination and connected to my main interest at the time: exploring the woods behind my house.

My mom and I lived in Pound Ridge, and I had taken to surveying the territory beyond our backyard. Once I crossed the tree line, I entered another world: a fir-canopied strip of land with a stream flowing through rocky banks and tiers of rooted earth abutting a ridge that seemed to touch the sky. I often pretended that I was exploring a great undiscovered place and wandered the area for hours, familiarizing myself with its contours. I would return to the house with artifacts — usually deer antlers and volcanic rock— and trained myself in rock-jumping challenges and ridge-scaling regimens in case a predator or rival appeared. Other times, I would simply sit on one of the boulders overlooking the stream and observe the natural goings-on as if I were a part of the wooded world, imagining I was a tree or rock or insect or the wind, earth, water, or just sound — anything but a kid stuck between two parents.

While my mom and I were in Pound Ridge, my parents still maintained some hope of a reconciliation. At first, my mom and I lived in the house with her boyfriend, Teddy, but she and I would regularly visit my dad together so they could talk. My dad dated other women, but it was understood that I shouldn’t tell my mom anything about that. Or, at the very least, I should wash the truth, as much as a six-year-old boy could.

I didn’t know why my parents had split — besides that each made the other sad and sometimes angry — and because they often attempted to make up, I wondered what the purpose of their separation was, the point of the distance between us. When my mom’s relationship with Teddy dissolved and we continued living in that far-eastern part of Westchester, I couldn’t fathom why we couldn’t be reconnected, why the bridge — which clearly still existed — couldn’t be crossed.

More than wanting my parents back together, I wanted the fluctuations and complications of their saga to cease. My rides with Uncle Lou, just like my meditative sessions in the woods, provided a welcome escape from their drama.

As we would drive in the stop-and-go traffic of semi-bucolic I-684 and onto the concrete plains of I-287, Uncle Lou would tell me stories of trekking through foreign woods as a soldier, surviving on meager rations of food, and idle conversations with other prisoners. Sometimes, he’d recount a serialized story of a boy and his dog—their adventures and the problems they solved—always ending with a teaser for the next installment when we arrived at my dad’s office.

Even though the particulars of those stories have been lost to memory, the rich tableau and the soporific feeling of those car rides have stayed with me. Uncle Lou’s words — even in his froggy, gruff tone — were like waves gently washing over me. And as the car crept along in traffic or droned over the Tappan Zee Bridge, as Uncle Lou recast the main characters and dark-wooded setting, I would often fall asleep.

One day, however, I was awoken by a jolt. At first, I thought I had just shifted in my sleep and banged my head, but, as my fog cleared, I saw that we had gotten into an accident. Uncle Lou asked if I was okay, and that’s when I noticed that my neck burned and my head hurt. When I said I was fine, he exited the car to talk to a man who kept raising his arms and shaking his head. The hood of Uncle Lou’s car was crumpled. I thought about getting out to see what had happened, but the idea of leaving the car and its cocoon of apples and stories was frightening. Outside the car was a world of asphalt, steel and concrete barriers shaped like warped spines. It was the adult world — always infringing on what felt good to me.

Whether the accident was his fault — maybe his reactions weren’t fast enough or his vision not good enough — or the other driver was to blame, those Friday afternoon trips with Uncle Lou ended. I still saw him at my dad’s office and at family events, so at the time I didn’t register the loss of our meaningful routine. He didn’t mention it either. I imagine he buried any sadness, channeling it into excited greetings, tight hugs and conversations about my life whenever I saw him. He would cup one of my hands between his as if to protect the time we had together, recognizing its limits, and knowing that, at that moment, we were together and this was real.

Years later, I remember vividly when my dad called to tell me that Uncle Lou had passed away. Coincidentally, I was sitting in the front passenger seat of another grandfatherly sedan, but this time while traveling with my mom and stepfather through Southern California traffic. I cried like I hadn’t in years —raw and unguarded — as I recalled my car trips with Uncle Lou and finally felt the loss that had been lingering, waiting to be acknowledged.

***

Justin Goldberg is a writer and editor, living in North Carolina. He is working on a memoir.

Beautiful writing.

I love Uncle Lou.

What a touching reminder for all of us! Savor the memories. Beautifully written

This story elicited smiles and tears—the depth of feelings of the child telling the story, but, only as adult may able to put the words to the feelings. Love Uncle Lou. He seemed so real & stable all the while parents are very confusing! The apple a metaphor for what Justin was experiencing—thank you for telling your story!

WONDERFUL!!!! florence proto

All right, Goldberg, time for a follow up about Florence Proto. Whatever that backstory might be.